A Meta-analytic Review of Aerobic Fitness and Reactivity to Psychosocial Stressors

- Original Inquiry Article

- Open Access

- Published:

Aerobic Fitness Level Affects Cardiovascular and Salivary Alpha Amylase Responses to Acute Psychosocial Stress

Sports Medicine - Open volume ii, Commodity number:33 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Good physical fitness seems to help the individual to buffer the potential harmful impact of psychosocial stress on somatic and mental health. The aim of the nowadays study is to investigate the role of physical fitness levels on the autonomic nervous system (ANS; i.e. middle rate and salivary alpha amylase) responses to astute psychosocial stress, while decision-making for established factors influencing individual stress reactions.

Methods

The Trier Social Stress Exam for Groups (TSST-Chiliad) was executed with 302 male person recruits during their showtime week of Swiss Army basic training. Heart rate was measured continuously, and salivary alpha amylase was measured twice, before and after the stress intervention. In the same week, all volunteers participated in a physical fitness test and they responded to questionnaires on lifestyle factors and personal traits. A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to determine ANS responses to acute psychosocial stress from physical fitness examination performances, controlling for personal traits, behavioural factors, and socioeconomic data.

Results

Multiple linear regression revealed three variables predicting fifteen % of the variance in heart rate response (expanse nether the individual middle charge per unit response curve during TSST-G) and four variables predicting 12 % of the variance in salivary alpha amylase response (salivary alpha amylase level immediately subsequently the TSST-G) to acute psychosocial stress. A potent performance at the progressive endurance run (loftier maximal oxygen consumption) was a significant predictor of ANS response in both models: depression area under the eye rate response curve during TSST-G as well as low salivary alpha amylase level after TSST-G. Further, loftier muscle ability, non-smoking, high extraversion, and low agreeableness were predictors of a favourable ANS response in either 1 of the two dependent variables.

Conclusions

Proficient physical fitness, especially good aerobic endurance capacity, is an important protective factor confronting health-threatening reactions to acute psychosocial stress.

Key Points

- 1.

Aerobic fitness level affects cardiovascular responses to acute psychosocial stress.

- 2.

Aerobic fitness level affects alpha amylase responses to acute psychosocial stress.

- 3.

Present results support the cantankerous-stressor adaptation hypothesis, saying that even if psychological coping with stress remains unaffected, the various preparation-induced adaptations in the organization of the ANS of an aerobically fit person influences physiological responses to acute stress.

Background

Psychosocial stress has a harmful impact on somatic and mental health [1, 2]. In order to better individual resistance to psychosocial stress, regular physical activity seems to be an effective strategy [3–7]. This relation is based on similarities between physiological processes during physical and psychological stress [8, 9]. A situation which is perceived as stressful, independent of whether the source is physical [10, 11] or psychological [12, 13], leads to an contradistinct activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) centrality and the autonomic nervous organisation (ANS). Considering regular physical training has been shown to diminish the reactivity of the HPA axis and ANS during exercises [x, 11], a cross-adaptation to psychological stress is assumed [14]. To test the cross-stressor adaptation hypothesis [15] discussed above, many studies investigated the relation betwixt physical activity behaviour and psychological stress reactivity. All the same, the wellness-promoting issue of regular physical exercise on stress reactivity is about probably based on a combination of two effects: amend psychological resources resulting in improved psychological coping with stress and (2) reduced physiological reactivity to stress [14]. De Geus and Stubbe believe that even if psychological coping with stress remains unaffected, the various training-induced adaptations in the organization of the ANS and its target organs influence the design and intensity of physiological responses to stress [fourteen]. To investigate that hypothesis, the influence of concrete fitness on stress responses should exist investigated while decision-making for physical action behaviour and potential stress-influencing factors. As potential stress-influencing factors, personality- and behaviour-related factors were just selected when prior studies have demonstrated their relation to stress reactions. Some evidence suggests that personality traits, resilience, smoking habits, educational level, and migrating background are influencing perception and responses to psychosocial stress [16–20].

It is the aim of the present study to investigate the part of physical fitness level on ANS (i.east. heart rate and salivary alpha amylase) responses to acute psychosocial stress, while controlling for established factors influencing private stress reactions. Using the framework of the cross-stressor adaptation in the present study, the hypothesis was that the individual concrete fettle level modifies the physiological stress responses to not-exercise stressors. Lower baseline heart rate (Hour), stronger Hour reaction to non-exercise stressors, faster Hr recovery after termination of a non-exercise stressor, and lower salivary alpha amylase (sAA) immediately afterwards the non-exercise stressor are expected in physically well-trained subjects.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Volunteers were recruited amid the 693 immature men who started their mandatory military service in the Swiss War machine garrison located in Aarau, Switzerland. This sample is representative of the healthy young Swiss male population. In total, 651 recruits (94 %) gave their informed consent to volunteer in the scientific project, approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Canton Aargau, Switzerland (registration number 2011/008). All research was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. For the nowadays study, 302 recruits were randomly selected from the pool of volunteers to accept part in a psychosocial stress test. In the outset week of basic military training (BMT), the selected volunteers participated in an acute psychosocial stress test (Trier Social Stress Test for Groups [TSST-Thousand]), while 60 minutes was monitored continuously and saliva samples were collected immediately earlier and after the TSST-G for analyses of sAA. In the same week, all volunteers participated in a physical fitness examination and they responded to a battery of questionnaires regarding lifestyle factors and personal traits.

Stress Provocation

To induce acute psychosocial stress, the TSST-G was applied as stated past Bösch et al. [21] and first described past von Dawans et al. [22]. The TSST-G is an established, standardized performance test protocol that combines a high level of social-evaluative threat and uncontrollability to provoke psychosocial stress [21]. In the present written report, four participants were seated side by side to each other but separated by privacy protection walls. After ii min of baseline measurement, the upcoming job was introduced and subjects were allowed to prepare themselves for 2 min. Then, a simulated expert panel entered the room and turned on video cameras to brand the subjects believe that they were beingness videotaped. Each participant had ii min to introduce himself for a mock job interview. After completion of the iv short interviews, participants were asked to perform a mental arithmetic chore consisting of continuous subtraction, as quickly and accurate as possible. Afterwards each mistake, subjects had to restart from the get-go. Again, this examination took ii min for each of the four participants. Finally, the TSST-K was followed by half dozen min of recovery measurement.

Information Collection

Heart rate was continuously measured during the stress examination using an ambulatory electrocardiography system (Equivital Arrangement; Hidalgo, Cambridge, U.k.). Data were edited manually (VivoSense, Vivonoetics, San Diego, CA), and the average HR (in beats per minute [bpm]) was calculated for 2-min time intervals.

Salivary alpha amylase samples were collected immediately earlier and after the TSST-G. Participants were requested to gently chew on a Salivette (Sarstedt, Sevelen, Switzerland) for i min. The samples were stored at −twenty °C until analyses were conducted in the biochemical laboratory of the Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. The activity of sAA was analysed with a kinetic colorimetric examination using assay kits from Roche (Roche 11555685 blastoff-Amylase Liquid acc, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and an automatic analyser (Biotek Instruments, Lucern, Switzerland) with the software KC4 (Roche).

Concrete fitness was assessed using the Swiss Army physical fitness test battery [23]. The test battery contained a progressive endurance run (PER) to measure aerobic endurance chapters; a standing long jump (SLJ) and a seated shot put (SSP) to mensurate muscle power of the lower and upper extremities, respectively; a torso muscle strength test (TMS) to measure trunk muscle fettle; and a ane-leg standing test (OLS) to mensurate residue. The PER is a paced running examination, conducted on a 400-one thousand outdoor track according to the protocol adult by Conconi et al. [24] and evaluated using the concluding running velocity. Based on PER, the maximal oxygen consumption (V̇O2max) can be estimated using the formula past Wyss et al. [23]. The SLJ was performed from the gym hall floor onto a mat of 7-cm top. The SSP was performed as a two-kg brawl chest pass while sitting upright on a demote with the back touching a solid wall. In the TMS, the subjects had to hold an isometric body position (prone bridge) [25] for as long equally possible, while lifting their feet alternately. In OLS, participants had to keep position on 1 leg as long as possible while closing their eyes subsequently 10 s and laying their caput back while keeping the eyes airtight after 20 s. Time was measured for the left and correct legs separately, and the sum of both was used as a value for balance ability. Precise descriptions of the five tests were published elsewhere [23]. To assess anthropometry, body peak was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Seca model 214, Seca GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) and body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg on a calibrated digital balance (Seca model 877, Seca GmbH, Hamburg, Frg).

Data on personality traits, behavioural factors, and socioeconomic data were assessed by questionnaires. Information on the personality of participants were assessed using the German language version of the NEO Psychological Personality Inventory with 240 items and five-bespeak Likert calibration by Ostendorf and Angleitner [26]. Participants' resilience was assessed by the brusque version of the resilience scale (RS) [27], consisting of eleven items answered on a 7-point Likert scale. The High german version of the perceived stress questionnaire (PSQ) [28] with twenty items and a iv-indicate Likert scale was used to detect subjects' perceived chronic stress level. Physical activity behaviour was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ brusk) [29], and participants were classified as inactive, partly active, unregularly active, regularly active, and trained. Further, questions that were previously not validated about smoking habits, migration background, and educational level were used to group participants as smoker and non-smoker and Swiss citizens with and without a migration background and in iii categories of educational levels (lower secondary schoolhouse, upper secondary schoolhouse, and high school).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 22.0, IBM, Chicago, IL) with a level of significance of p < .05 to indicate statistical significance. Group results are presented every bit mean ± standard deviation. A multiple linear regression was run to predict ANS responses to acute psychosocial stress from concrete fettle test performances, decision-making for personal traits, behavioural factors, and socioeconomic data. As a dependent variable representing magnitude of cardiovascular response, the area under the individual HR response curve (AUCg) was calculated using a trapezoid formula [30], as has been done earlier to correspond physiological responses [5]. As a dependent variable representing sympathetic sAA reactivity, the increase from pre- to post-TSST-Yard as well every bit the sAA level determined immediately after the TSST-G (i.due east. postal service level) was used. The latter variable was included because baseline levels ordinarily plant a menstruum of combined sympathetic and, probably more important, parasympathetic activity, and the latter tin positively influence amylase activity itself [31, 32]. Therefore, it is unclear which of both variables, the change value or the value determined afterwards the stress examination, better reflects sympathetic stress reactivity. The potential independent predicting variables are listed in Table ane. Regression analyses were performed twofold, with the same event: by backwards elimination and past systematic inbound of the variables in the club of the force of the association with the dependent variable. Variables which did not predict the dependent variable significantly (p > .05) were removed from the model. The assumptions of linearity, not-collinearity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, unusual points, and normality of residuals were met. The issue size of predicting variables was calculated according to Cohen [33] as \( {f}^two=\frac{\left({R}_{\;\mathrm{including}}^2-{R}_{\;\mathrm{excluding}}^two\right)}{1-{R}_{\;\mathrm{including}}^2} \). Cohen termed an effect size of .02, .15, and .35 as small, medium, and large, respectively. Fettle variables remaining in the final regression model were used to stratify volunteers in four operation groups of a like number of participants for each performance examination. For case, the 25 % of participants with the best PER performances were stratified to the starting time quartile, representing volunteers with highest aerobic fitness level, while the fourth quartile represented those 25 % with the everyman aerobic fitness level. 60 minutes reactivity was calculated past the absolute difference in HR values in the 2-min segment before the TSST-G and the ii-min segment of the interview task during the TSST-Thou (first HR-peak). HR recovery was calculated past the absolute deviation in HR values in the 2-min segment of the mental arithmetic task (2nd Hr-acme) and the 2-min segment starting 6 min after the end of the TSST-M. Group comparisons were conducted using independent sample t tests. Furthermore, repeated measures ANOVA was used to investigate furnishings of grouping, fourth dimension, and group × time interaction on 60 minutes and sAA levels during TSST-G. In all the presented data, the Mauchly test showed that the supposition of sphericity has been violated; therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser estimate was used to report repeated measures ANOVA results.

Results

Participants

Complete information on 219 male person recruits (73 % of the total sample of selected volunteers) with a mean age of 20.ii ± 1.1 years, a body size of 177.8 ± vi.6 cm, and a trunk mass of 74.9 ± xi.3 kg were registered. Volunteers' mean values and proportions for all independent variables are presented in Table 1. Participants' V̇O2max was significantly correlated to the SLJ, and SSP operation (r = .190 and −.190, p < .01, respectively), while the 2 latter ones were positively correlated to each other every bit well (r = .180, p = .007). Further, participants' V̇Oiimax was significantly correlated to their physical activity and smoking behaviour as well equally to their educational level (r = .163, −.186, and .170, p < .05, respectively), and their smoking addiction was correlated with their educational level and agreeableness (r = .347, and .236, p < .001, respectively). Participants that were classified as insufficiently physically agile (less than 150 min of moderate or 75 min of vigorous physical activities per week) had a lower V̇O2max level, compared to the participants who were sufficiently physically active (48.87 ± 4.46 and l.99 ± 5.ten ml/kg/min, p = .002).

Cardiac Response to Acute Stress

A multiple linear regression predicting HR-AUCg revealed performances at the PER, at the SLJ, and smoking mental attitude every bit significant independent variables (Table 2). The many other covariates—BMI, physical activity behaviour, resilience, personality traits, educational level, and migration background—proved statistically insignificant. The assumptions of linearity, non-collinearity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, unusual points, and normality of residuals were met by the used model (Table two). The variables in the concluding regression model significantly predicted 60 minutes-AUCg, F = 12.626, p < .001, adj. R 2 = .150. Regression coefficients, kept on measurement calibration, standard errors, and their respective 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) can be derived from Table 2.

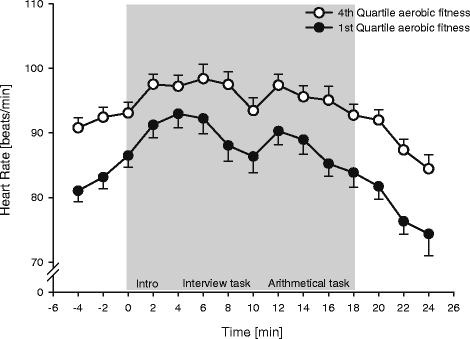

The strongest influence on total magnitude of Hr response to acute stress was plant for aerobic fitness (Cohen's effect size of f ii = .12). Participants were, therefore, stratified into four groups of aerobic fitness, with 55 volunteers in the first quartile of aerobic fitness (V̇O2max of 55.eight ± 1.6 ml/kg/min) and 54 volunteers in the quaternary quartile (V̇O2max of 43.3 ± two.half dozen ml/kg/min). The HR responses to the TSST-G in these groups are presented in Fig. 1. As Fig. 1 indicates, a repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect on HR by the factors group (F = x.622, p = .002) and time (F = 19.271, p < .001), but non by the interaction between grouping and fourth dimension (F = i.618, p = .137). HR values were significantly different (p < .05) between groups at baseline. However, Hr reactivity in participants of loftier aerobic fettle level was stronger (+11.9 ± ten.1 bpm) than that in participants of low aerobic fitness level (+6.4 ± nine.1 bpm, p = .004). HR recovery was not different between the two groups (−eleven.iii ± 10.8 and −9.four ± seven.2 for first and fourth quartiles, respectively, p = .370).

HR before, during, and after the TSST-G among volunteers of loftier and low aerobic fettle. Values are presented every bit hateful ± SEM for each 2-min time interval. The first quartile represents subjects of high aerobic fitness; the fourth quartile represents subjects of depression aerobic fitness. Each of the 15 time-segments in the figure represents information from all 219 subjects. HR heart rate, TSST-K Trier Social Stress Examination for Groups

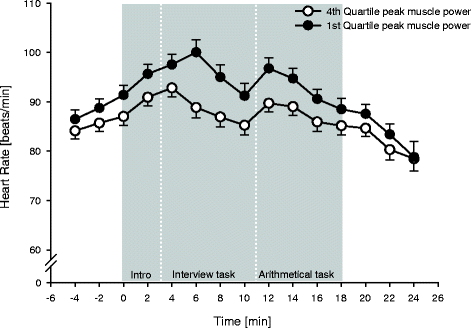

The same comparison, using SLJ performance to stratify volunteers in different groups, resulted in Fig. 2. The 52 volunteers in the starting time quartile of the lower extremity muscle ability had a ameliorate SLJ functioning (2.5 ± 0.ane m) than that of the 56 volunteers in the fourth quartile (two.1 ± .1 grand). The HR response to the TSST-G in those two SLJ functioning groups is presented in Fig. 2. Every bit Fig. 2 indicates, a repeated measures ANOVA showed a meaning main consequence on HR past the factors group (F = four.469, p = .037) and time (F = 24.560, p < .001) too as the interaction between group and time (F = 3.259, p = .003). Hour values of the 2 operation groups were not different before and subsequently the TSST-Thousand intervention. However, HR reactivity in the start quartile of SLJ performances was stronger (+13.5 ± 13.3 bpm) than that in participants of the fourth quartile of SLJ performances (+4.viii ± 9.viii bpm, p = .001). Hr recovery was non different between the two groups (−12.0 ± 9.4 and−nine.8 ± 8.2 for the first and 4th quartiles, respectively, p = .221).

Hr earlier, during, and after the TSST-Yard amid volunteers of high and low musculus power in the lower extremities. Values are presented as mean ± SEM for each 2-min time interval. The commencement quartile represents subjects of high muscle ability. The quaternary quartile represents subjects of depression muscle power. Each of the 15 time-segments in the figure represents data from all 219 subjects. HR center rate, TSST-1000 Trier Social Stress Test for Groups

Smokers and non-smokers had the aforementioned baseline and recovery HR earlier and later the TSST-G. However, not-smokers showed a stronger 60 minutes reaction to the TSST-Yard (+10.5 ± 9.7 bpm) compared to smokers (+6.0 ± 7.6, p = .001).

Subjects' HR-tiptop levels during the interview chore (first 60 minutes-elevation) and the mental arithmetic task (second HR-pinnacle) were comparable (93.2 ± xvi.4 and 92.2 ± xiv.six bpm, p = .166). However, 60 minutes during those 2-min time intervals were higher (p < .001) than the chore-specific boilerplate HR over 8 min (91.6 ± fourteen.4 bpm during interview chore and 89.vii ± 13.2 bpm during arithmetic task).

sAA Response to Acute Stress

A multiple linear regression predicting the modify in salivary blastoff amylase (ΔsAA) values (increase in sAA level from pre- to mail-TSST-Chiliad) revealed performance at the OLS (B = .764, SE = .313, β = .170, t = ii.437, p = .016) and educational level (B = 13.079, SE = 4.127, β = .223, t = three.169, p = .002) as the simply significant independent variables. The variables in the concluding regression model explained 5 % of the variance in the ΔsAA values, F = ii.825, p = .012, and adj. R ii = .050.

A multiple linear regression predicting the sAA stress response to astute stress (sAA level after TSST-G) revealed performance at the PER, performance at the OLS, and the two personality traits "extraversion" as well every bit "conjuration" as relevant contained variables (Table three). The variables in the final regression model significantly predicted the sAA stress response, F = 8.796, p < .001, and adj. R two = .124. Regression coefficients, kept on measurement scale, standard errors, and their corresponding 95 % CIs can exist derived from Table iii.

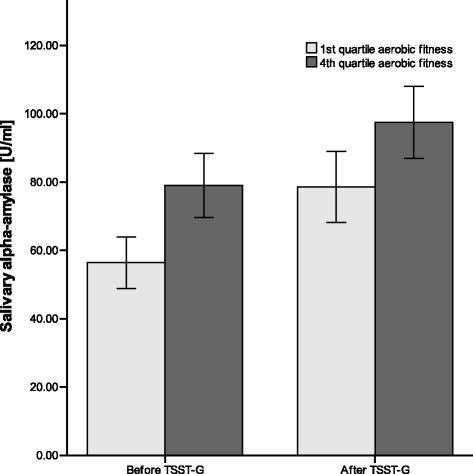

Aerobic fettle was the just variable represented in the models, predicting 60 minutes and sAA responses to acute stress. Cohen'south effect size for PER as a predictor variable for the sAA stress response was f 2 = .03. The sAA values immediately before and after the TSST-G of recruits in the quartile of the lowest and highest aerobic fettle level are presented in Fig. 3. A repeated measures ANOVA with time (earlier and after TSST-G) as within-subjects factor and group affiliation as between-subjects factor showed a significant main event on sAA values by the factors group (F = x.369, p = .002) and time (F = 16.434, p < .001), only not for the interaction between group and time (F = 0.474, p = .492).

Salivary alpha amylase stress response in subjects of high and low aerobic fettle. Values are presented equally hateful ± SEM. Salivary alpha amylase was investigated immediately before and after the Trier Social Stress Examination for Groups (TSST-G). The offset quartile represents subjects of high aerobic fitness. The fourth quartile represents subjects of low aerobic fitness

Give-and-take

HR and sAA responses to acute psychosocial stress were shown to be dependent on recruits' physical fettle level, even when controlled for concrete activity behaviour and further relevant covariates. Therefore, the present written report supports the hypothesis of De Geus and Stubbe [14] that the various fitness-related adaptations in the system of the ANS and its target organs influence the pattern and intensity of physiological responses to stress, even if psychological coping with stress remains unaffected. Hour-AUCg was predicted by performances at the PER, SLJ, and regular smoking behaviour (Table ii). sAA stress responses were predicted past operation at the PER and OLS, every bit well equally by values representing the personality trait "extraversion" and "agreeableness" (Table three). Surprisingly, physical activity behaviour did not remain in the regression models, and just a weak relation to aerobic fitness was demonstrated (r = .163). That might exist due to the methodological disadvantages of self-reported questionnaires to assess physical activity [34]. In the following sections, the relationship of each predicting variable to 60 minutes-AUCg and sAA is discussed and compared to results of previous studies.

Cardiac Response to Acute Stress

The cumulative 60 minutes-AUCg value, as an index of the full HR output across the measurement flow, has been shown to be helpful to detect relevant variables, predicting cardiac response to acute stress [v]. However, HR-AUCg is strongly dependent on three aspects of HR development, on baseline 60 minutes, HR reactivity during TSST-G, and on HR recovery later on TSST-G. A healthy Hr reaction to stress tin exist described as low baseline HR, strong Hr reaction to acute stress, and fast HR recovery subsequently the acute stress situation [35]. A low baseline or resting eye rate was found in the review of Cooney et al. [36] to be strongly related to reduced incidence of cardiovascular diseases. A meta-assay about the relation between cardiovascular responses to acute stress and health revealed that a greater reactivity to stress was associated with poor cardiovascular health status [37]. However, included studies ordinarily considered changes in systolic and diastolic claret pressure as a marker for cardiovascular responses. Studies examining 60 minutes reaction to acute stress, instead, showed higher increases in Hour during acute stress in salubrious subjects. For example, in the report of Jackson et al. [13], subjects with lower risk of hypertension showed a 60 minutes increment of 20 bpm during mental arithmetic task compared to their peers with higher hazard of hypertension with a HR increase of 12 bpm. This observation can be explained by the evolutionary importance to get prepare to fight or flying equally presently every bit a threat appears. Furthermore, with regard to the law of initial values (assuming that the magnitude of responses is dependent of the initial baseline level, i.e. a loftier baseline is associated with a reduced reactivity), i could wait a college HR reactivity in subjects with lower baseline levels [38]. Nevertheless, further evidence arose showing a decreased HR reaction to acute stress to be related with worse wellness [35, 39, 40]. Therefore, one has to presume that both exaggerated as well as blunted cardiovascular reactivity tin can exist maladaptive [41, 42]. Finally, a fast HR recovery from acute stress was consistently associated with reduced cardiovascular risk status [37].

A good aerobic endurance capacity is related to healthy cardiac reaction to acute stress. Two out of three criteria of a healthy 60 minutes reaction on stress were demonstrated in volunteers in the first quartile of PER operation. They showed a baseline 60 minutes of 10 bpm lower than that of volunteers in the quaternary quartile of PER. Further, they revealed a significantly greater Hour reactivity to acute stress compared to the lowest quartile of cardiovascular fitness. A meta-regression analysis of 73 studies investigating laboratory stress came to the same conclusion that cardiorespiratory fitness is related to greater reactivity and amend recovery of HR responses [43]. In dissimilarity, other meta-analyses institute a decreased psychological stress reactivity in relation with physical fitness (e.one thousand. Forcier et al. [44]), contributing to the inconsistency in the literature.

Based on the present data, muscle power might exist related to a salubrious cardiac reaction to acute stress as well (strong HR reactivity and fast HR recovery). Subjects of low and loftier SLJ performance showed the same baseline HR earlier the stress task. However, during the TSST-M, the group of subjects with high SLJ operation showed a stronger Hr reaction, and a trend of faster 60 minutes recovery (Fig. 2), resulting in larger HR-AUCg values. It can be ended that subjects with high musculus power showed two out of three criteria of a healthy reaction to stress (potent Hour reactivity and fast HR recovery) [35] compared to subjects with depression muscle power. Based on prior studies on stress perception, we conclude that college musculus power might atomic number 82 to healthier physiological reactions to stress as well as to lower perceived stress level likewise [45–47]. However, to the noesis of the authors, the relation between anaerobic fitness, or musculus strength, and physiological responses to non-preparation-related, acute psychosocial stress is not sufficiently investigated yet. Therefore, further studies in this field are necessary to discuss the results demonstrated in the present report.

Smoking is related to an unhealthy cardiac reaction to acute stress. In understanding with our results, Child and Wit [48] demonstrated smaller relative HR reactivity during a TSST for smokers, compared to non-smokers. Therefore, the ability to adequately react to a stressor seems reduced in smokers. Authors of prior studies suggest that smoking causes a transient but too a long-term reduction in vagal cardiac control in young people [48, 49].

The many other covariates—BMI, physical activity behaviour, resilience, personality traits, educational level, and migration background—proved statistically insignificant in the multivariate regression analysis of the present written report.

sAA Response to Acute Stress

Nater and Rohlender [50] demonstrated in their review that the saliva enzyme sAA is a sensitive biomarker for stress-related changes in the trunk that reflects the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. Therefore, they emphasized that sAA level is a proficient marker to stand for stress reactions. Balodis et al. [51] demonstrated a significant positive relation between subjective stress perception (anxiety reactivity) and the increment in sAA from pre- to mail service-TSST-G besides equally the level of sAA subsequently the TSST-G. In conclusion, high ΔsAA and high mail service-sAA values are related to increased perception of threat in a stressful state of affairs.

A proficient aerobic endurance chapters might be positively related to healthy sAA reactivity on astute stress. A repeated measures ANOVA analysis demonstrated aerobic fettle-group affiliation to be a significant principal event on sAA, with depression physical fitness related to increased sAA values. This result was previously observed in other studies and explained by the cross-stressor accommodation hypothesis. Co-ordinate to the cross-stressor adaptation hypothesis, in physically trained individuals, lower sAA responses to stressors other than the training do can be expected [15, 52].

In the present study, volunteers of high-residue power (assessed by OLS) showed college ΔsAA values over the astute stress period likewise as higher sAA values after the TSST-Chiliad. No similar results of other studies exist. However, this positive relation was non expected and does non become in line with the results of Nedeljkovic et al. [53].

Educational level might be related to stress reactivity besides. However, the results of dissimilar studies are not consistent. In the nowadays study, a positive relation between educational level and ΔsAA response on astute stress was found. In accordance with our written report, Fiocco et al. [54] found higher cortisol reactivity on acute stress in subjects with high educational level. In dissimilarity to our results, a study on stress perception derived reduced perceived stress level in subjects of higher didactics [20].

Extraversion and agreeableness remained in the regression model, predicting sAA level after TSST-Thousand. The present results indicate that high extraversion leads to reduced sAA reactivity, while high agreeableness leads to increased sAA values after the TSST-G. Therefore, loftier extraversion and low agreeableness are favourable personality traits in terms of favourable reaction to acute psychosocial stress. Prior studies showed the same relation between extraversion and perceived psychological stress [xvi, 55]. However, these studies showed no significant relation betwixt agreeableness and perceived psychological stress.

Relation Between Physical Activity, Physical Fitness, and Stress Reactivity

Regular participation in physical activity (e.1000. practice) is expected to influence strength, balance, and aerobic capacity, three aspects of physical fitness [34]. Exercise results in astute and chronic changes in central and autonomic nervous organisation activity, the contracting muscles, and the heart, with several mechanisms being involved, including the practice pressor reflex, arterial and cardiopulmonary baroreceptors, and the central command (for an overview see Fisher et al. [56]). As addressed past the cross-stressor hypothesis [15], concrete activity, exercise training, and concrete fitness are related to increased parasympathetic and decreased sympathetic activeness, myocardial hypertrophy, increased stroke volume, reduced blood pressure during residual, and an increase in muscle capillary density and force [57]. Additionally, beneficial furnishings were reported with regard to mental health (due east.1000. depression and feet disorders) [58], cognitive role, and the central nervous organization, with greater white and grey matter volume [59–61], mainly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (PFC) [34]. Furthermore, an changed association with key [62] and cardiac oxidative stress [63] and inflammation [64] was found. All together, these findings support the health-protecting and wellness-promoting effect of concrete activity.

When comparing brain and peripheral structures and mechanisms affected by exercise, a wide overlap with structures involved in stress reactivity becomes evident. In fact, the neurophysiological model introduced by Lovallo [42] assumes that differences in stress reactivity derive from differences in three organizational levels. Level I includes the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the limbic organisation. Level II addresses the hypothalamus and the brain stem consisting of output signals to the body and feedback to level I. Level Three includes the peripheral tissues, with difference reflecting amidst other things' variations in autonomic or endocrine output.

Therefore, exercise (or fitness), which is related to better mood and PFC characteristics, seems to bear witness higher activity in level I, eliciting stronger inhibitory control over limbic structures crucial in the command of cardiac activity [65]. When confronted with stressors, the top-downwardly modulation from the PFC to the central nucleus of the amygdala is disinhibited, resulting in multiple mechanisms being activated or inhibited (level Ii) leading to an increment in HR (level III). These mechanisms include direct activation equally well every bit disinhibition of sympathoexcitatory neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla, and inhibition of the nucleus of the solitary tract with subsequent inhibition of vagal motor outputs in the nucleus ambiguous and dorsal vagal motor nucleus [65]. This results in an increase of sympathetic and a decrease in parasympathetic activity and, therefore, a rise in HR. In subjects with higher physical fitness, 1 tin assume higher inhibitory control from the PFC and, therefore, college parasympathetic and lower sympathetic activity during rest. Still, when stressed, a fitter subject field has the potential to show a larger disinhibition compared to a less fit subject, since the latter probably experiences less inhibition past the PFC already under residual, limiting the capacity to farther inhibit the activity of the limbic system. Every bit a effect of the larger disinhibition in fitter subjects, the net reduction in vagal and increase in sympathetic action can be larger, allowing for a stronger 60 minutes reactivity to stress. These considerations might explain our findings of lower Hour under rest and stronger Hour stress reactivity in participants with strong aerobic fitness.

Limitations

In order to measure the 18-carat stress reactivity of recruits before the influence of whatever preparation, reactivity to the TSST-G had to exist assessed during their commencement week of BMT. Since we had just five days to investigate volunteers' stress reactivity, it was not possible to perform the time-consuming TSST-Chiliad with all the 651 volunteers. However, we were able to investigate 302 randomly chosen volunteers.

Due to organizational reasons, we were not able to provide threescore min to adapt participants to the laboratory setting, equally recommended for the assessment of psychoneuroendocrine baseline information [51]. Unfortunately, due to the brusk adaptation menses, some subjects probably did non reach a calm resting state of mind when sAA baseline data was assessed immediately earlier the TSST-G.

Salivary samples were only taken twice. More sAA samples before, during, and afterward the TSST-G would have been more meaningful. Possibly, the peak in sAA response was not assessed due to our study blueprint. However, more salivary samples would have distracted participants from the situation, causing a psychosocial stressful state of affairs.

The order of active participation of the iv subjects during the mock job interview and mental arithmetical chore was not recorded. In future studies, this information should exist recorded in gild to compare physiological reactions while actually performing the stress-inducing task and while passively attending and observing the others being stressed.

The nowadays study group does only represent young, healthy men. Our results cannot exist generalized per se for women, older men, and physically or mentally ill populations.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that good physical fitness—especially, good aerobic endurance capacity—is an important protective factor against wellness-threatening reactions to acute psychosocial stress. Cardiovascular fettle remains a significant predictor variable, even when controlled for the most important influencing factors to individual stress reactions. These results have important implications for individuals only also organizations providing mentally and physically enervating jobs. Employers should back up and offering access to physical endurance training for their staff, especially in settings where employees regularly accept to cope with stressful situations. In determination, regular and good concrete preparation of individuals and employees to increase their cardiovascular fitness is not simply of import for their physical health merely also their ability to adequately react to acute psychosocial stress situations.

Abbreviations

- ANS:

-

Autonomic nervous arrangement

- AUCg:

-

Area under the curve

- BMT:

-

Basic military preparation

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- IPAQ:

-

International Concrete Activity Questionnaire

- OLS:

-

One-leg standing test

- PER:

-

Progressive endurance run

- PFC:

-

Prefrontal cortex

- PSQ:

-

Perceived stress questionnaire

- RS:

-

Resilience calibration

- sAA:

-

Salivary alpha amylase

- SLJ:

-

Standing long jump

- SSP:

-

Seated shot put

- TMS:

-

Trunk muscle strength exam

- TSST-G:

-

Trier Social Stress Test for Groups

- V̇O2max:

-

Maximal oxygen consumption

- ΔsAA:

-

Alter in salivary alpha amylase

References

-

Ehlert U, Gaab J, Heinrichs M. Psychoneuroendocrinological contributions to the etiology of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and stress-related actual disorders: the function of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal centrality. Biol Psychol. 2001;57(1-3):141–52. doi:S0301051101000928.

-

Vanitallie TB. Stress: a risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism. 2002;51(vi Suppl i):40–5. doi:ameta0510s40.

-

Dishman RK, Jackson EM, Nakamura Y. Influence of fitness and gender on blood pressure responses during active or passive stress. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(5):568–76. 10.1017.S0048577202394071.

-

Rimmele U, Zellweger BC, Marti B, Seiler R, Mohiyeddini C, Ehlert U, et al. Trained men show lower cortisol, heart charge per unit and psychological responses to psychosocial stress compared with untrained men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(6):627–35. doi:S0306-4530(07)00086-viii.

-

Rimmele U, Seiler R, Marti B, Wirtz PH, Ehlert U, Heinrichs M. The level of physical activity affects adrenal and cardiovascular reactivity to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(2):190–8. doi:ten.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.023.

-

Dishman RK, Berthoud HR, Berth FW, Cotman CW, Edgerton VR, Fleshner MR, et al. Neurobiology of practise. Obesity. 2006;14(3):345–56. doi:14/3/345.

-

Petruzzello SJ, Jones Ac, Tate AK. Affective responses to astute practice: a test of opponent-process theory. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1997;37(3):205–12.

-

Holmes DS, Roth DL. Association of aerobic fitness with pulse rate and subjective responses to psychological stress. Psychophysiology. 1985;22(5):525–ix.

-

Hull EM, Young SH, Ziegler MG. Aerobic fitness affects cardiovascular and catecholamine responses to stressors. Psychophysiology. 1984;21(3):353–lx.

-

Deuster PA, Chrousos GP, Luger A, DeBolt JE, Bernier LL, Trostmann UH, et al. Hormonal and metabolic responses of untrained, moderately trained, and highly trained men to 3 practise intensities. Metabolism. 1989;38(two):141–8. doi:0026-0495(89)90253-9.

-

Luger A, Deuster PA, Kyle SB, Gallucci WT, Montgomery LC, Gold Prisoner of war, et al. Acute hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to the stress of treadmill exercise. Physiologic adaptations to physical preparation. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(21):1309–15. doi:10.1056/NEJM198705213162105.

-

Moyna NM, Bodnar JD, Goldberg Hr, Shurin MS, Robertson RJ, Rabin BS. Relation between aerobic fitness level and stress induced alterations in neuroendocrine and immune function. Int J Sports Med. 1999;20(2):136–41. doi:10.1055/s-2007-971107.

-

Jackson EM, Dishman RK. Hemodynamic responses to stress amongst blackness women: fitness and parental hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(seven):1097–105.

-

de Geus EJ, Stubbe JH. Aerobic exercise and stress reduction. In: Fink Thou, editor. Encyclopedia of stress. New York: Academic; 2007. p. 73–8.

-

Sothmann MS, Buckworth J, Claytor RP, Cox RH, White-Welkley JE, Dishman RK. Exercise preparation and the cross-stressor accommodation hypothesis. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1996;24:267–87.

-

Penley JA, Tomaka J, Wiebe JS. The clan of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2002;25(6):551–603.

-

Southwick SM, Vythilingam M, Charney DS. The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: implications for prevention and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;ane:255–91. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143948.

-

Parrott AC. Smoking cessation leads to reduced stress, merely why? Int J Addict. 1995;30(11):1509–sixteen.

-

Parrott AC. Cigarette smoking: effects upon self-rated stress and arousal over the day. Addict Behav. 1993;xviii(4):389–95. doi:0306-4603(93)90055-Due east.

-

Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economical status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51. doi:10.1177/135910539700200305.

-

Boesch M, Sefidan S, Ehlert U, Annen H, Wyss T, Steptoe A, et al. Mood and autonomic responses to repeated exposure to the Trier Social Stress Exam for Groups (TSST-1000). Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;43:41–51.

-

von Dawans B, Kirschbaum C, Heinrichs Grand. The Trier Social Stress Exam for Groups (TSST-1000): a new research tool for controlled simultaneous social stress exposure in a group format. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:514–22.

-

Wyss T, Marti B, Rossi S, Kohler U, Mäder U. Assembling and verification of a fitness exam battery for the recruitment of the Swiss ground forces and nation-wide use. Swiss J Sports Med Sports Traumat. 2007;55(4):126–31.

-

Conconi F, Ferrari M, Ziglio PG, Droghetti P, Codeca Fifty. Determination of the anaerobic threshold by a noninvasive field test in runners. J Appl Physiol. 1982;52(four):869–73.

-

Wunderlin S, Roos Fifty, Roth R, Faude O, Frey F, Wyss T. Trunk muscle forcefulness tests to predict injuries, attrition and military ability in soldiers. J Sports Med Phys Fettle. 2015;55(5):535–43. doi:R40Y9999N00A150043.

-

Ostendorf F, Angleitner A. NEO-Persönlichkeitsinventar nach Costa und McCrae: Revidierte Fassung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2004.

-

Schumacher J, Leppert Thousand, Gunzelmann T, Strauss B, Brähler E. Die Resilienzskala - Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der psychischen Widerstandsfähigkeit als Personmerkmal. Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother. 2005;53(1):xvi–39.

-

Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, Walter OB, Kocalevent R-D, Weber C, et al. The perceived stress questionnaire (PSQ) reconsidered: validation and reference values from different clinical and healthy developed samples. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(ane):78–88. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000151491.80178.78.

-

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB.

-

Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH. 2 formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus fourth dimension-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(seven):916–31. doi:S0306453002001087.

-

Bosch JA, Veerman EC, de Geus EJ. α-Amylase as a reliable and user-friendly measure of sympathetic activity: don't start salivating but yet! Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(iv):449–53. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.12.019.

-

Busch L, Sterin-Borda L, Borda Eastward. An overview of autonomic regulation of parotid gland activity: influence of orchiectomy. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;182(three-4):117–28.

-

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–nine.

-

Erickson KI, Leckie RL, Weinstein AM. Physical activity, fitness, and greyness matter volume. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35 Suppl 2:S20–8.

-

Carroll D, Phillips Air conditioning, Chase K, Der G. Symptoms of depression and cardiovascular reactions to astute psychological stress: evidence from a population study. Biol Psychol. 2007;75(ane):68–74. doi:S0301-0511(06)00258-4.

-

Cooney MT, Vartiainen E, Laatikainen T, Juolevi A, Dudina A, Graham IM. Elevated resting heart rate is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease in healthy men and women. Am Middle J. 2010;159(4):612–9. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.029. e3.

-

Chida Y, Steptoe A. Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status: a meta-assay of prospective evidence. Hypertension. 2010;55(four):1026–32. doi:x.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146621.

-

Berntson GG, Uchion BN, Cacioppo JT. Origins of baseline variance and the law of initial values. Psychophysiology. 1994;31(2):204–10.

-

Kupper N, Denollet J, Widdershoven J, Kop WJ. Cardiovascular reactivity to mental stress and mortality in patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(5):373–82.

-

Phillips Air conditioning. Blunted cardiovascular reactivity relates to depression, obesity, and cocky-reported wellness. Biol Psychol. 2011;86(2):106–xiii.

-

Carroll D. A brief commentary on cardiovascular reactivity at a crossroads. Biol Psychol. 2011;86(two):149–51.

-

Lovallo D. Practise low levels of stress reactivity signal poor states of health? Biol Psychol. 2011;86(two):121–8.

-

Jackson EM, Dishman RK. Cardiorespiratory fitness and laboratory stress: a meta-regression analysis. Psychophysiology. 2006;43(one):57–72. doi:PSYP373.

-

Forcier M, Stroud LR, Papandonatos GD, Hitsman B, Reiches One thousand, Krishnamoorthy J, Niaura R. Links between concrete fitness and cardiovascular reactivity and recovery to psychological stressors: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2006;25(6):723–39.

-

Taylor MK, Markham AE, Reis JP, Padilla GA, Potterat EG, Drummond SP, et al. Physical fitness influences stress reactions to extreme military preparation. Mil Med. 2008;173(8):738–42.

-

Tsutsumi T, Don BM, Zaichkowsky LD, Delizonna LL. Physical fitness and psychological benefits of strength preparation in community dwelling older adults. Appl Man Sci. 1997;sixteen(half-dozen):257–66.

-

Kettunen O, Kyrolainen H, Santtila M, Vasankari T. Physical fitness and volume of leisure time physical activity relate with low stress and high mental resources in young men. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2014;54(4):545–51. doi:R40Y2014N04A0545.

-

Childs E, de Wit H. Hormonal, cardiovascular, and subjective responses to acute stress in smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;203(1):1–12. doi:ten.1007/s00213-008-1359-5.

-

Hayano J, Yamada M, Sakakibara Y, Fujinami T, Yokoyama G, Watanabe Y, et al. Short- and long-term effects of cigarette smoking on eye rate variability. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65(1):84–8. doi:0002-9149(ninety)90030-five.

-

Nater UM, Rohleder Northward. Salivary alpha-amylase as a non-invasive biomarker for the sympathetic nervous organisation: current country of enquiry. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(iv):486–96. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.01.

-

Balodis IM, Wynne-Edwards KE, Olmstead MC. The other side of the bend: examining the human relationship betwixt pre-stressor physiological responses and stress reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(9):1363–73. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.03.011.

-

Zschucke East, Renneberg B, Dimeo F, Wustenberg T, Strohle A. The stress-buffering effect of astute exercise: evidence for HPA centrality negative feedback. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:414–25. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.019.

-

Nedeljkovic M, Ausfeld-Hafter B, Streitberger K, Seiler R, Wirtz PH. Taiji practice attenuates psychobiological stress reactivity—a randomized controlled trial in good for you subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(eight):1171–eighty. doi:ten.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.007.

-

Fiocco AJ, Joober R, Lupien SJ. Education modulates cortisol reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Exam in middle-aged adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(8-10):1158–63. doi:S0306-4530(07)00208-9.

-

Feizi A, Keshteli AH, Nouri F, Roohafza H, Adibi P. A cross-sectional population-based written report on the association of personality traits with anxiety and psychological stress: joint modeling of mixed outcomes using shared random effects arroyo. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19(9):834–43.

-

Fischer JP, Young CN, Fadel PJ. Autonomic adjustments to exercise in humans. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(2):475–512.

-

Longhurst JC, Stebbins CL. The power athlete. Cardiol Clin. 1997;xv(3):413–29.

-

Paluska SA, Schwenk TL. Physical activity and mental health: current concepts. Sports Med. 2000;29(3):167–fourscore.

-

Colcombe SJ, Erickson KI, Scalf PE, Kim JS, Rakash R, McAuley E, Elavsky Southward, Marquez DX, Hu Fifty, Kramer AF. Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2006;61(11):1166–70.

-

Erickson KI, Raji CA, Lopze OL, Becker JT, Rosano C, Newman AB, Gach HM, Thomposn PM, Ho AJ, Kuller LH. Physical activity predicts gray matter volume in belatedly adulthood: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Neurology. 2010;75(16):1415–22.

-

Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakahs RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L,… Kramer F. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(7):3017–22.

-

Gao L, Wang Due west, Liu D, Zucker IH. Exercise grooming normalizes sympathetic outflow by primal antioxidant mechanisms in rabbits with pacing-induced chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3095–102.

-

Bertagnolli Grand, Schenkel PC, Campos C, Mostarda CT, Casarini DE, Bello-Klein A, Irigoyen MC, Rigatto Thousand. Exercise training reduces sympathetic modulation on cardiovascular organization and cardiac oxidative stress in spontaneous hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(11):1188–93.

-

Hamer H, Sabia South, Derailed D, Shipley MJ, Tabak AG, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki Chiliad. Physical action and inflammatory markers over x years: follow-upwards in men and women from the Whitehall Ii Cohort Report. Ciculation. 2012;126(8):928–33.

-

Thayer JF, Lane RD. Claude Bernard and the center-encephalon connection: further elaboration of a model of neurvisceral integration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(2):81–eight.

Acknowledgements

We would similar to thank all volunteering recruits and their military commanders as well equally the school commander of the Swiss Armed Forces training schoolhouse Inf DD 142/143 of Kdo fourteen located in Aarau, Switzerland, who agreed to participate in this fourth dimension-consuming scientific projection.

Funding

This study received funding from the Federal Department of Defense, Civil Protection and Sports DDPS, Switzerland.

Authors' Contributions

TW was involved in the conception, data collection, analysis, manuscript writing and revision. MB and LR performed the primary role of the data collection and were involved in the data analysis and revision. CT prepared the theoretical background and was involved in editing the manuscript. KF performed the data analysis and revision. HA was involved in all aspects of this study, including conception, data collection, data analysis, and revision. RL was involved in the conception of the study, manuscript writing, and critical revision. All authors read and approved the last manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics Approving and Consent to Participate

The present study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Canton Aargau, Switzerland (registration number 2011/008). All subjects gave their informed consent to volunteer in the scientific projection. All research was performed in accordance with the upstanding standards of the Announcement of Helsinki.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you requite advisable credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and bespeak if changes were fabricated.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this commodity

Cite this article

Wyss, T., Boesch, M., Roos, L. et al. Aerobic Fitness Level Affects Cardiovascular and Salivary Alpha Amylase Responses to Acute Psychosocial Stress. Sports Med - Open up 2, 33 (2016). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s40798-016-0057-9

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s40798-016-0057-9

Keywords

- Physical fettle

- Physical activity

- Stress response

- Stress prevention

- Autonomic nervous arrangement

- Cross-stressor adaptation hypotheses

shoffnerbellordes.blogspot.com

Source: https://sportsmedicine-open.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40798-016-0057-9

Enviar um comentário for "A Meta-analytic Review of Aerobic Fitness and Reactivity to Psychosocial Stressors"